Click here to subscribe today or Login.

State troopers deal with bad behavior for a living. Evidently, a few might be guilty of it themselves.

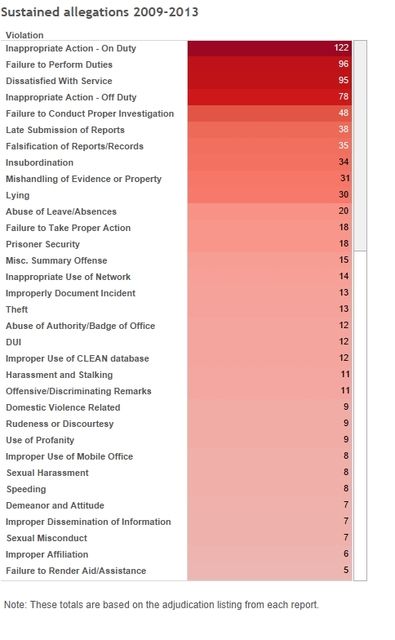

Internal investigators found proof of more than 1,000 allegations of misconduct from 2009 through 2014, according to annual reports, including many potentially serious violations like sexual misconduct, drunken driving, domestic abuse, criminal harassment and lying.

The Pennsylvania State Police provided names of 12 troopers who were fired for misconduct in the six-year period. During that time, more than 50 criminal violations by troopers were internally substantiated.

Many other offenses, including sexual misconduct and harassment, lying and drunken driving often call for automatic dismissal under agency policy.

“The 12 deadly sins,” said union official Ron Zona. “According to our contract, the proper discipline is termination.”

Lawsuits filed by troopers also allege cases of retaliation and cronyism in internal investigations, costing the state hundreds of thousands of dollars in court settlements.

The state police — which has some 4,700 sworn members and 1,850 civilian staff — does not publicly disclose investigation details, but does provide breakdowns of the types of investigations and outcomes in several years of internal reports obtained by PublicSource.

This examination of records provides a rare public look at how the agency sought to stamp out sexual misconduct following a major scandal in the force. However, the reports don’t say how and when problem troopers are punished.

While serious misconduct appears to be tied to relatively few troopers, allegations substantiated year after year involve violent and sexual misconduct in clear conflict with the agency’s mission to serve the Commonwealth.

See how we did our analysis.

Recent violations

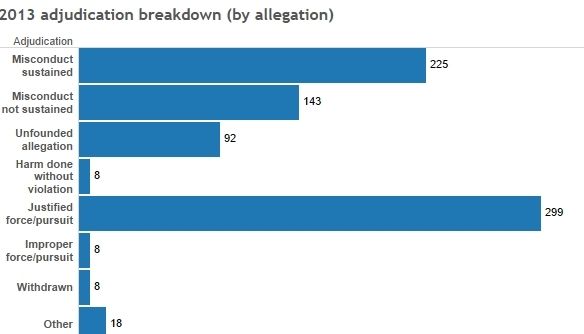

In 2013, the last year with a detailed report, internal investigators found proof of 225 misconduct allegations, according to that year’s adjudication listing.

The allegation listing shows at least 30 potentially serious violations, including criminal theft, criminal harassment, criminal forgery, sex on duty, sexual harassment, domestic violence and drunken driving.

One trooper can be investigated for several allegations, and some investigations can stretch across years.

The report doesn’t say whether allegations qualify as the so-called 12 deadly sins. The troopers union contract, however, mentions automatic termination for those categories if the conduct is considered to be serious enough.

A state police representative said matching specific internal allegations with the 12 offenses would require a manual search through years of paper records.

“Discipline cases are categorized by internal charges, not potential applicability to enumerated offenses,” Maria Finn, a police spokeswoman, wrote in an email.

A criminal violation does not mean a trooper was convicted of a crime. A district attorney may choose not to prosecute. Police internal investigations have a lower standard of proof.

The job description

The Pennsylvania State Police patrols state and federal highways across the commonwealth and serves as the primary law enforcement agency for much of the state, especially in rural areas that don’t have full-time police.

The agency was founded in 1905 and was the first law enforcement agency of its kind in the United States. With about 4,700 sworn members and 1,850 civilian staff, it remains one of the largest forces in the country.

Troopers are often better paid than local police, with salaries starting at $57,251 for new troopers, running to near and above six figures for veterans. By contrast, the starting salary for an officer in the Pittsburgh Bureau of Police is $42,548.

Troopers have difficult and dangerous jobs. Most of them do their work free of misconduct.

A single trooper was fired in 2013, according to the agency’s record. Court records link that trooper to an on-duty drunken driving violation in 2012.

Three troopers were fired in 2014. The state police would not say why.

However, one of those troopers was put on probation in 2012 for making harassing and lewd phone calls after a 2010 road rage incident, according to court records. Another terminated trooper had earlier filed an unsuccessful lawsuit against the agency for discrimination based on sexual orientation, according to court documents.

The list of terminated troopers does not account for all serious misconduct.

Former trooper Barry Searfoss was terminated last year after pleading guilty to a 2012 fatal drunken driving accident. No disciplinary action was taken because state law requires automatic termination of officers convicted of felonies and serious misdemeanors.

Other troubled troopers could have left or retired before being fired.

The listing of fired troopers is missing cases that began in 2008 or earlier. The state police could not provide those names.

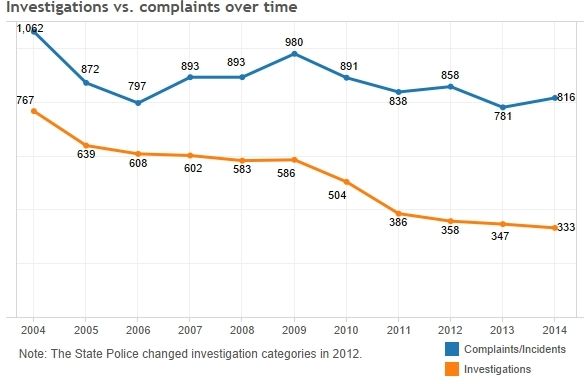

Annual disciplinary reports from 2004 through 2008 reveal more than 800 substantiated misconduct allegations.

From 2004 through 2013, an additional 1,000 allegations could be neither verified nor disproved by internal investigators.

The severity of misconduct can vary widely.

For instance, “harassment is one of those charges that could go from a mere warning to a criminal case,” said John “Rick” Brown, who retired in early 2010 as state police deputy commissioner of administration and professional responsibility.

Brown said a typical year might see 10 to 12 firings for misconduct, with minor fluctuation.

One or two firings for a year (or zero, as was recorded in 2010) seemed low to Brown.

Each case, of course, varies depending on the facts.

“[W]e conduct thorough, objective and complete investigations and do not believe there are any issues with the current process,” police spokeswoman Finn wrote.

A media representative from the Pennsylvania State Troopers Association, the troopers union, declined to comment on the disciplinary process.

See how we did our analysis.

Past sins

Internal discipline was once a point of major disgrace.

Despite early warnings, agency leadership failed for years to keep a predatory trooper from abusing numerous women and girls while on the job, a troubling and expensive scandal that led to the adoption of the current penalty system in 2005 — roughly four years after his criminal sentencing.

According to a state report, Trooper Michael Evans paid a prostitute for sex while on duty and took a nude picture of her against a patrol car; he was suspended for three days.

He also made a habit of rubbing his genitals in front of teenage girls. In one case, the girl’s parents complained, but the accusation was “unfounded” based on the strength of his character. Another girl reported him to a school counselor, which led to a criminal investigation.

Sexual misconduct allegations weren’t isolated.

A broader state investigation into sexual harassment and misconduct didn’t happen until one of the girls filed a lawsuit against police officials in 2003. The investigation revealed 89 cases of alleged sexual harassment and misconduct over a seven-year period by more than 100 troopers.

The Commonwealth settled with several of Evans’ victims for $6.3 million.

Three majors were investigated internally for sexual misconduct over the same period but not fired, according to a report by the Pennsylvania Office of Inspector General.

Two of the three majors — one who assaulted an administrative assistant in her home, and another who stalked and harassed a subordinate after their relationship ended — were allowed to retire, the report said. The third major, who repeatedly touched the buttocks of a secretary, went to a counseling session.

Fixing the system

The inspector general’s report said repeated, high-level violations showed that sexual harassment and misconduct were not treated seriously.

The state also hired Kroll Associates to examine internal discipline in a one-year, $250-an-hour monitorship.

The firm called for the state police to impose much harsher and more consistent penalties.

Following the Evans scandal, a new contract with the Pennsylvania State Troopers Association was negotiated, and, after arbitration, was amended to include crucial changes to disciplinary procedure.

First, the 12 enumerated offenses were established, setting in stone firm, automatic penalties for the most egregious violations. Future discipline would no longer be tied to past decisions.

Brown, who now runs a police consulting company called Transparency Matters, was given the job of overseeing state police compliance changes.

That work has been criticized as “capricious” and “Machiavellian,” he said, though he views his tenure as a success.

Crucially, he said, troopers understood that sexual misconduct was a firing offense.

“They say, ‘Hey look, if I touch a woman’s butt in the workplace, I’m gone,’” Brown said.

See how we did our analysis.

Fixed or failing?

So, after several million dollars, a state investigation, a third-party review and overhauled discipline rules, have the problems been fixed?

Zona, who is president of Fraternal Order of Police Lodge #62, said he thinks discipline is more fair now — and less heavy-handed — than eight or 10 years ago.

“We’ve gone through a lot of ironing out of different issues,” he said.

Sometimes firings stick, he said. Sometimes they’re overturned.

The inspector general’s office continued oversight of investigations for many years and said for a final time in 2012 that it was satisfied with the agency’s handling of misconduct.

A representative from the inspector general’s office said there are no ongoing concerns.

But Susan Mahood, a Pittsburgh lawyer who has represented several troopers in personnel lawsuits, said she’s seen disparities in treatment in internal investigations “numerous times.”

“There is a big difference in how you’re treated depending on who you are,” she said.

In one of her lawsuits — which she could not discuss due to a confidentiality agreement — documents claim Jeffrey Shaw, the former head of internal affairs for Western Pennsylvania, became the target of an investigation after ordering an inquiry in late 2008 over alleged interference by a barracks commander in a child molestation case involving a prominent businessman, who was never charged.

Now retired, Shaw was fired, abruptly rehired and eventually awarded a $450,000 settlement.

Trooper Cheryl Amodei-Mascara, who also sued and is now retired from the force, was accused of making an anonymous complaint about the molestation investigation, and officials wanted Shaw to divulge her identity. According to Amodei-Mascara’s suit, her mother was the source of that complaint.

Amodei-Mascara, who previously won damages for retaliation, was awarded $225,000.

In another case, Trooper Jolando Hinton claims a bogus internal affairs investigation led to his firing after years of racial and other discrimination by superiors. That lawsuit is still open, and the state has said the termination was due to many acts of “malfeasance.”

What’s troubling is that such allegations appear only in lawsuits, not in any public disciplinary process.

For instance, the revelation that three lieutenants admitted to taking trips to Thailand to have sex with prostitutes only appeared publicly in an employment lawsuit by another trooper. The FBI investigated, though no charges were filed.

Police transparency is a major issue, said Mary Catherine Roper, deputy legal director for the ACLU of Pennsylvania.

Public trust would increase, she said, if citizens had clear information on specific officers who misbehave.

“There is no question that people get really angry when they hear about abuses by police officers,” Roper said. “The way to solve that is not to hide abuses.”

See the original story at http://publicsource.org/node/5108.