Click here to subscribe today or Login.

SECO, Ky. — Mines built this company town. Jack and Sandra Looney hope vines — the wine grapes growing on a former strip mine in the hills above — will help to draw visitors here.

Their Highland Winery — housed in the lovingly restored “company store” — pays tribute to coal-mining’s history here, as do their signature wines: Blood, Sweat and Tears.

“The Coal Miner’s Blood sells more than any of them,” Jack Looney says of the sweet red.

The couple have converted the store’s second and third floors into a bed and breakfast and restored a couple dozen of the old coal company houses as rentals.

Seco, like so many Central Appalachian communities, owes its existence to coal — its very name is an acronym for South East Coal Company. But as mining wanes, officials across the region are looking for something to replace traditional jobs and revenues.

In some of the poorest, most remote counties, about the only alternative people can come up with is tourism — eco-, adventure, or, as with the Looneys, historical and cultural. There are mining museums, festivals, wilderness adventures. Sub-regions have been rechristened with alluring names like the Hatfield-McCoy Mountains or the PA Wilds.

Proponents point to the region’s assets, its natural beauty, its distinctive mountain character. But others note the paradoxes: Environmental degradation alongside unspoiled areas, a history of poor education that for decades didn’t preclude high-paying jobs, an away-from-it-all feel partly caused by a lack of good roads and other infrastructure.

A dubious savior?

For all but a lucky few places with both assets and access, recent studies and spending data suggest, tourism may be a dubious savior.

“It’s kind of really odd that economic practitioners push tourism to be a propulsive industry when it has such low wages,” says Suzanne Gallaway, an adjunct professor at the University of North Carolina-Greensboro

Sociologist Rebecca Scott, author of a book on mountaintop removal in her native West Virginia, says that state, the only one wholly included in the government’s definition of Appalachia, is “caught between the condition of being an extraction economy, a sacrifice zone, and yet having most of its sort of long-term successes in tourism being around nature-based tourism.”

Gallaway, who teaches at UNCG’s Bryan School for Sustainable Tourism and Hospitality, found that while tourism and hospitality accounted for 16 percent of all jobs in the region, those sectors produced just 7 percent of the wages.

“I wouldn’t put all of my eggs in that basket,” she says.

A 2012 report compiled for West Virginia’s Division of Tourism found that spending and hospitality employment have been slow to grow in many counties.

An exception was Harrison County, where direct tourism spending has more than doubled since 2004 — to $142 million — and hospitality employment has increased by more than 50 percent. But those numbers can be deceiving. Many rooms in the area’s hotels are being occupied by workers drilling in the nearby Marcellus shale formation, as coal has been replaced by hydraulic fracturing to extract natural gas, says county commission president Ron Watson.

According to the economic report, tourism-related jobs in the Hatfield-McCoy Mountains — the marketing label for a cluster of coal-producing counties — actually dropped from 1,400 to 1,300 from 2004 to 2012.

Carole Morris, who was head of cultural tourism for the state of Kentucky before opening her own consultancy, says there’s a fine line between squashing initiative and encouraging pipe dreams.

Pennsylvania case

A few years ago, Morris shared a $100,000 Appalachian Regional Commission grant to consult with several “distressed” counties. One of her clients was Forest County, Pennsylvania.

For generations, the county, dominated by the Allegheny National Forest, was a popular vacation destination for blue-collar workers, earning it the nickname “Pittsburgh’s playground.” But as manufacturing waned and tastes changed, Morris found, locals were left with a “tired product.”

A local planning group suggested rebranding the county as a “gateway” to the Lumber Heritage Region and the PA Wilds. The trick, Morris and team wrote in their action plan, was for the county to stay “true to its heritage of ‘the place to get away from it all,’ and respect its rural roots while moving into the new marketplace for tourism.”

In Kentucky, as environmentalists fight to protect areas not disturbed by mining, some longtime residents are trying to make the most of what the coal industry has left behind.

In its day, Lynch was the largest coal company town in the world. At its height in the 1940s, more than 10,000 people lived there; today, Lynch’s population hovers around 730.

But a mine there, Portal 31, has been given new life. Visitors can ride a miniature train several hundred feet into the hillside as a guide and animated exhibits illustrate mining history. Several company buildings have been restored.

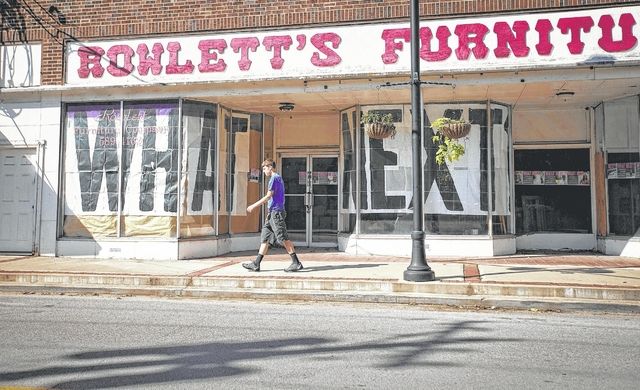

Down the road in Benham, the former company store now houses the Kentucky Coal Mining Museum.

Tourism vs. education

Museum Curator Phyllis Sizemore says the exhibition mine saw a record number of visitors in July: Just 1,033.

“I don’t look to tourism exactly as a savior,” she says. “I look at education as a savior.”

People like the Looneys know that doing tourism in an out-of-the-way place, especially one that’s been blasted and carved up, is an uphill battle.

When they bought it, the old company store was little more than a shell. They also had to petition for a vote to legalize alcohol sales in “dry” Letcher County. More than a decade after opening, Looney’s construction business is still lending the winery money.

The couple started the venture as a way to keep their daughter in the mountains. She eventually started her own vineyard with her husband in Lexington.

Jack Looney still hasn’t given up on Jean coming back to run things in Seco. If not, then there are always the grandkids.

“Maybe somebody will before I get too old to quit fooling with it.”